Search the term “Great American Novel” online, and a Google-assisted artificial intelligence will spit out worthy titles: The Great Gatsby, Huckleberry Finn, Invisible Man, Moby Dick, and To Kill a Mockingbird. Google the Great American Songbook, and you’ll recognize musical staples like “Over the Rainbow” and “The Christmas Song.”

But if you search “great American movie,” an odd assortment of classics, movies with the word “America” in the title, and even one picture that is now almost unavailable on any streaming service is presented.

For some reason, no canonical discussion of the Great American Movie exists.

Yes, the American Film Institute has ranked the 100 best American movies, but that is a separate conversation. To distinguish a picture as the “best” is to deem it the most excellent, effective, or desirable type or quality. Seeking out the “best” American movie is to find the most impressive and effective combination of the cinematic arts—story, performance, craftsmanship, etc. So, it’s unsurprising that Citizen Kane is often at the top of the list.

But the Great American Movie is different.

Like Huckleberry Finn, Invisible Man, or even Sam Cooke’s “A Change Is Gonna Come,” the quest for the Great American Movie is defined not by technical or storytelling excellence. Rather, it's the search for the most effective exploration of America’s soul. Stick with me; this is not just an abstract philosophy here. This doesn’t mean the Great American Movie can’t be a masterwork in the cinematic arts and sciences (because it should be). But its primary motivation should be using those tools to analyze our history and purpose dramatically. If there is such a picture, it would reveal in every frame both the beautiful and the aspirational, the flawed and the uncomfortable.

There are three criteria for what makes the Great American Movie.

Must take place in America;

Must be produced by a predominately American production company;

Must embody the American experience.

And as young as the art of filmmaking is, there already seems to be a clear contender for the title of the Great American Movie: The Searchers (1956, dir. Ford).

Don’t know this one? Well, you should.

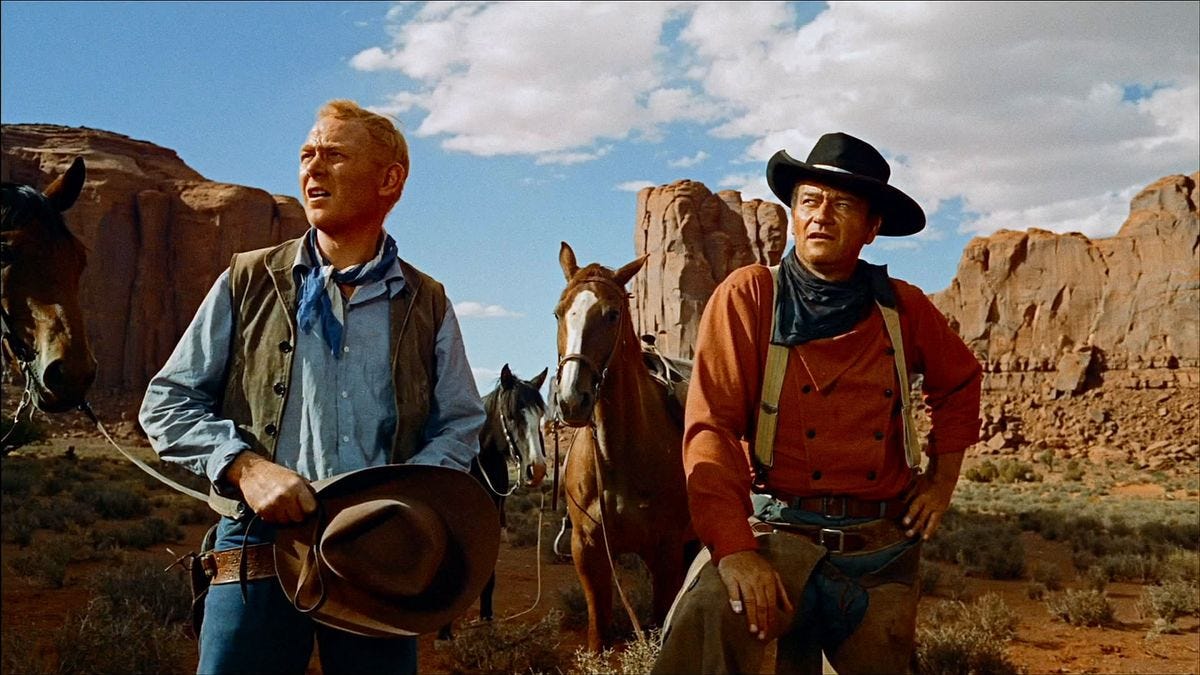

Based on a 1954 novel of the same name by Alan Le May— itself inspired by the 1836 kidnapping of Cynthia Ann Parker by Comanche warriors— The Searchers tells the story of a middle-aged Civil War veteran and his nephew who spends years looking for his niece, abducted in a home raid by Comanche tribesman. It’s a film by a master craftsman at the height of his power. John Ford, at this point in his career, was already the most honored director in Academy history: The Informer, How Green Was My Valley, The Grapes of Wrath, and The Quiet Man.

Starring John Wayne in an uncharacteristically dark performance, the film was a critical and commercial success upon release. It grossed $3.7 million domestically in its first year; Look magazine praised it as a “Homeric odyssey.” Admired on its release, it is now beloved. Spielberg, Scorsese, Bogdanovich, and Lean all have cited it as influencing their work. The American Film Institute named it the 12th greatest American movie and the greatest American Western. Entertainment Weekly agreed. Across the pond, the British Film Institute's Sight & Sound magazine ranked it the seventh-best film of all time in a 2012 international survey of film critics. Their 2022 poll ranked it fifteenth. In 1989, it became one of the first 25 films selected for preservation in the National Film Registry as “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”

Like hundreds of movies released yearly, The Searchers easily checks two of the three requirements to be the Great American Movie. It takes place in America—Texas and the American southwest, to be exact—and is produced by an American production company (Warner Bros. and Ford’s Argosy Pictures). Easy peasy. But the third criterion, which weeds out almost all other pictures, save for The Searchers, is that they must embody the American experience.

Tons of ink have been spilled examining what exactly that experience is. So it’s fruitless to try to do so here. Suffice it to say that, generally speaking, the “American experience” is the search for political and social community and the societal struggle with racism.

We see the search for community play out across American history. The first European settlers saw the coastline of the North Atlantic as a safe haven from persecution in their homelands. To them, America was a religious community. By the time of the Revolution, thirteen separate colonies bonded together to become a larger political community. With the opening of the West in the mid-nineteenth century, immigrants and pioneers made the dangerous trek toward the Pacific in search of creating new communities where wealth and security belong to the strongest. The dominating sentiment behind all these movements? That the individual meant more than the state; that community was built on common interests and values, not the class status you were born to. This opened up the promise of America to everyone, but it has also been used as a bludgeon.

On the other side of the equation are the existing political and religious systems of the Native people. For three centuries, the Native peoples and tribes saw their communities threatened, eliminated, and, eventually, forcefully integrated into the ones brought over from across the sea. Tragically, those who came to America to escape persecution became the persecutors.

The Searchers offers a nuanced exploration of these themes and ideas, which are so subtle at times that they might as well be subliminal. It is not surprising that the Great American Movie would be a Western. As Richard Brody recently wrote for the The New Yorker:

Westerns are an inherently political genre, for the obvious reason that they depict (or distort or interrogate) American history. But they are also political in that they show the birth of the polis itself—the institutions of modern urban society, with their laborers, clerks, merchants, teachers, sheriffs, entertainers. Where philosophers from Plato to Rousseau sought to imagine the development of civil society from first principles, the makers of Westerns—John Ford, Howard Hawks, Raoul Walsh—showed it being created from the ground up, by hands-on labor.

Ford’s films, regardless of the genre, have an abiding interest in upholding the virtues of the everyman, their communities, and what holds people together. It’s seen in a microcosm in Stagecoach and transplanted to locations such as Wales and Ireland in How Green Was My Valley and The Quiet Man. To Ford, there is strength in a people’s union—and the West is the most natural canvas to explore it. In The Searchers, Ford and company spend valuable film stock exploring the customs and virtues of the frontier community, itself the greatest force for creating the American mythos.

For instance, the courtship between Martin Pawley and Laurie Jorgensen, while disjointed from the shocking urgency of the main storyline, gives us a glimpse into what it means to find community in desolate places. Here are strong-willed individuals, stepping out from the protection of society to build new communities in the way they see fit. It’s not hard to see where the myth of the West came from, or why it was perpetuated for so long. Yes, it’s a white Christian community, but that is a historical fact, not a comment on Ford’s own social or political views.

This community is shaken to its core with the arrival of John Wayne’s Confederate veteran Ethan Edwards—who lusts for his brother’s wife and abhors his nephew, Martin, for his one-eighth Comanche blood—and the raiding of the Edwards homestead. Murdered are Ethan’s brother and sister-in-law. Murdered are all the children, save for his niece, Debbie. Ethan, too, seeks community after many years away. The murder of his brother and the woman he pined for from afar destroyed that ideal he had hoped to return to. This says nothing, mind you, about the racism that animates most of his actions throughout the movie.

Figures like Ward Bond’s Rev. Capt. Clayton embody the tension felt in the community. While disgusted by the heinous acts Edwards commits, they feel powerless to stop him. Clayton and others abandon Edwards in his efforts, but that alone does not stop the search. When they do try to stop him, necessity and time demand they turn their attention to the Comanche.

And it’s here where the commentary around The Searchers becomes even more intriguing. In the twenty-first century, the depiction of the Comanche tribe and Native peoples has increasingly come under fire. Among them is the criticism that the portrayal of Comanche chief Scar by Henry Brandon, a blonde-haired, blue-eyed actor, is problematic. This is valid. The condemnation of the sequence in which Martin Pawley accidentally “buys” a Native wife is also entirely fair. I myself squirm at the scene, which belittles this poor woman for the sake of what, frankly, feels like an extended joke about the intelligence of her people. But disregarding the movie or its deeper meaning because the mores of the twenty-first century are widely different than those of the previous generations is a disservice to the art.

Those who would ignore The Searchers’ scathing exploration of racism because of these elements are the same who would discredit Huckleberry Finn’s condemnation of antebellum slavery because of its uncomfortable use of the n-word. For a piece of art to be listed among the “Great Americans,” it has to confront the harshest realities of our past. Chief among them is racism. It has to be ugly and unsettling. After all, many parts of our shared history are. Holding up the bad equally against the good, we see in the greatest American art the promise and pitfalls of being a democratic people, one centered around the “proposition” (to quote Mr. Lincoln) that all people are created equal.

The Searchers warns what the absence of that proposition does to the heart of man. Imperfectly told by today’s standards of Native representation, the potency of Ethan Edward’s arc cannot be denied. His five-year odyssey of unequivocal hate is populated with horrific acts too numerous and gruesome to mention, the least of which is his grotesque treatment of Martin Pawley. Here’s one instance:

For most of the picture, it does not seem interested in punishing the character for his vile acts. Ambivalent might be the right adjective. Yes, characters like Pawley and Ward Bond’s Rev. Capt. Clayton attempt to stop him from carrying through his most horrific acts of madness, but no sentence is handed down. But that in no way means Ethan’s madness goes unpunished. Take a moment to watch the final scene of the movie.

Having saved his niece, Ethan receives no absolution. His madness drove everyone away. And, although he accomplished his mission, he finds no forgiveness for what he did along the way. The community he returned to at the beginning of the film—the one Ford spent so much time and film stock giving us a glimpse into—eventually leaves him behind.

Ford’s ending of The Searchers does not vindicate the actions of its racist protagonist. It gives him a punishment worse than death. In the first clip from the movie, Ethan maliciously shoots out the eyes of a Comanche corpse killed during a gun battle. Comanche tradition believes that without eyes, they cannot enter the spirit land and must wander forever between the winds. Ethan’s hatred and bigotry towards the Comanche, his rejection of human equality, blinded him. The film’s ending condemns Ethan to the same fate as the one he gave that Comanche corpse—to be exiled from his community and wander the West aimlessly and alone.

The rejection of equality is the rejection of community. The worst of America destroys the promise of her best. And for her to be the best, she must confront and cast out the worst. As filmmaker Domino Rene Perez wrote for the British Film Institute:

The iconic image of Ethan Edwards framed in the doorway, the expanse of the West stretching behind him, is as lyrical as it is telling. A relic of the past, he cannot cross over the threshold into the civilised world. He has helped to preserve a world he cannot be a part of any longer. Racist and unyielding, Ethan is not likeable and his redemption seems impossible. But Ford holds audiences in his visual and narrative thrall to the very end so that when the door shuts on Ethan, it's hard not to think about those who get left behind when the world moves on.

The Searchers is a deeply ambivalent movie until the last shot. Framing John Wayne in that doorway turns the movie into what Scorsese has called “a ghost picture,” and turns an ambivalent story into a counterculture exploration of the evil lurking in the heart of America. With The Searchers, Ford poetically exposes the noblest and ugliest parts of this curious political project, making a movie that is deeply political, deeply human, and uniquely American.

Its problems in the twenty-first century notwithstanding, Ford and company hold up a mirror to our nation and its history. In The Searchers, we see America for what it is: a beautiful contradiction. Majestic and awe-inspiring, dark and corrupted, ambivalent and moral.

That is why it is the Great American Movie.

Reader, what do you think is the Great American Movie? Let us know in the comments below!

Excellent analysis! Along with The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, I consider The Searchers to be John Wayne's finest Western and probably his greatest movie. The characters of Ethan Edwards and Tom Doniphon are similar in that they both are necessary to tame the West and deal with the savagery of the frontier, but neither one is fit to govern the society that replaces it. This is shown in TMWSLV in the development of Doniphon and Rance Stoddard (Jimmy Stewart), as it becomes clear that it's Rance more than Doniphon who is needed to establish a civilized nation. It's Doniphon, though, whose brutality is needed to defeat Valance as the necessary pretext to that civilization. So too in The Searchers. It's Edwards who is driven to find Debbie, no matter what the cost to the family or to himself. Edwards is the blunt instrument who can confront and defeat the savagery he encounters. But Edwards also knows that he can't be part of the civilization to which he returned Debbie. He's a creature of the frontier, so he declines to step over the threshold, instead returning to the realm from which he came at the film's beginning.