The Decidedly Mixed ' Life' of the 'Materialists' 'Scheme' | Review Roundup

Reviewing a trio of mid-budget adult flicks courtesy of Celine Strong, Wes Anderson, and Mike Flanagan

Summer movie seasons are often dominated these days by rampaging dinosaurs, people in spandex, and children’s entertainment. That’s true for this year, too. Since Memorial Day weekend, the biggest hits have been Tom Cruise defying death (again) for our amusement and Disney’s live-action remake of Lilo & Stitch. And while we’re approaching a dynamite streak of F1: The Movie, Jurassic World: Rebirth, Superman, and Fantastic Four all within five weeks of each other, there have been three pictures that have stood out from the pack thus far.

The movies in question — The Phoenician Scheme (dir. Wes Anderson), Materialists (dir. Celine Strong), and The Life of Chuck (dir. Mike Flanagan) — have nothing in common. They do not look, sound, or feel alike. Their genres do not criss-cross, nor are they geared towards the same audiences. As movies, they are as far apart as one can be from another. Yet some tiny but non-insignificant thread tangentially connects them.

All three movies seem interested in examining and subverting what we value in the modern world. This results in either rejecting twenty-first-century idols or recognizing that they have a place alongside the simpler things of life.

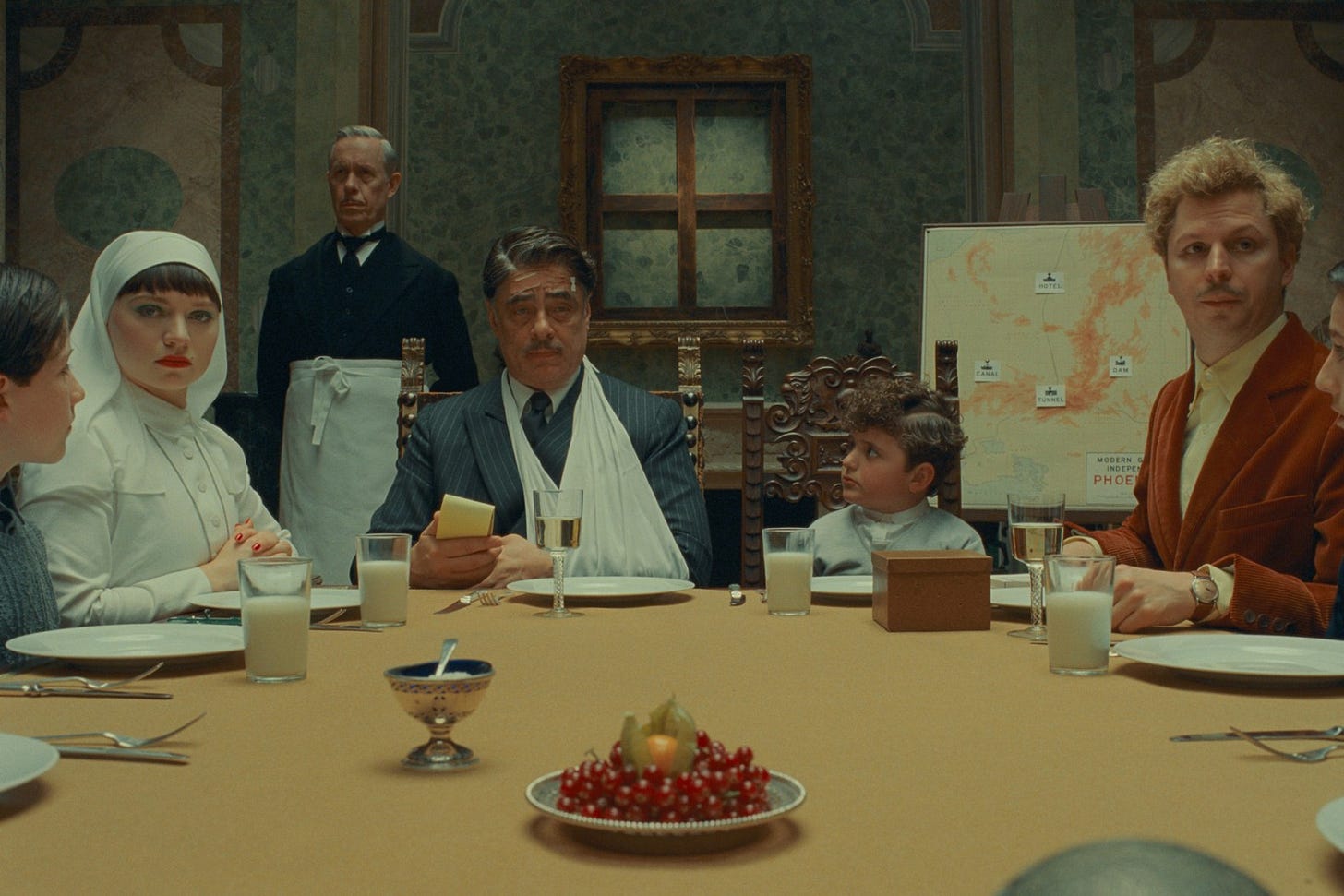

Case in point: Anderson’s espionage dark comedy The Phonecian Scheme, wealthy businessman and arms smuggler Zsa-zsa Korda (Benicio Del Toro) appoints his only daughter, a nun (Mia Threapleton), as sole heir to his estate and bets his entire fortune on a risky scheme to overhaul the infrastructure of the Mediterranean with slave labor. If successful, his wealth will be secured and multiplied for the next century. To him, life is wealth.

In Song’s romance Materialists, Dakota Johnson’s Lucy works as a professional matchmaker in New York City. She and her colleagues view finding love like it’s a Hinge algorithm, forced to mine through her clients’ desires from the perfect partner: good-looking, well-educated, and what’s the other one? Oh, rich. Filthy rich. To her, dating is a game, the people are the chess pieces, and she never expected to be a sap enough to play it herself.

In the science fiction drama The Life of Chuck (which won the Toronto Film Festival’s People’s Choice Award), a younger version of the titular character (Benjamin Pajak) wishes to learn how to dance for the Fall Fling. And he’s good at it. Really good. But his grandfather and guardian (Mark Hamill), a man of logic and mathematics, dismisses the young man’s passions for dance and extols the virtues of numbers and their place in every facet of life. Chuck dances at the fling, sure, but he spends his life as an accountant yearning for a chance to express himself truly. To his curmudgeon grandpa, life is numbers.

These cold worldviews are confronted and changed; each in a unique way, but all of them life-affirming. Del Toro’s Zsa-zsa realizes that the love he has for his religious daughter is worth more than a century’s worth of wealth. Not only that, but her faith is worthy of admiration and aspiration.

Johnson’s Lucy is confronted with a choice between a Hinge equivalent of a perfect man (Pedro Pascal) and an old flame (Chris Evans). The character of Chuck (eventually played by Tom Hiddleston) is given a moment in the last few months of his life to do the very thing that his grandfather dismissed. In doing so, he showed that he contained multitudes.

Each character learns that their lives, for better or for worse, are more than the cold, impartial, unfeeling social mandates we are handed today. In fact, they all seem to be rejections of how we live life in some capacity. But let’s be clear, the similarities stop there.

The quality of the movies themselves is mixed, to be kind, ranging from good to fine to outright failure. It is strange to try to juggle reviewing three movies at once, so please read on with indulgence as I hopscotch through the rest of the piece.

Phoenician is the strongest of the trio after what I believe was a backward slide for the Oscar-winner Wes Anderson with his lesser flicks, Asteroid City and The French Dispatch. It has a better sense of space and motion than his immediate predecessors, particularly Asteroid City, which often visually felt like a parody of a Wes Anderson film, and has a much bigger heart, too. And while I will be the first to admit that Anderson’s ultra-staged style of filmmaking is not my cup o’ tea, there is no denying that his restraint here serves the dark comedy and its touching father-daughter story.

It also has the best cast assembled this year, which I will not write out but encourage you to Google if you’re interested. My word. Don’t expect this to be in conversation for Anderson’s best films, but do anticipate consensus that this is a solid entry in his filmography and a charming anecdote to the blockbuster fare.

Celine Song offers another recommended summer tonic. Hot off her acclaimed, Oscar-nominated romance Past Lives, she keeps to the same genre with Materialists but with a much different approach. While the former keeps the yearning simmering under the surface, the latter joyfully wears its influences on its sleeve. While it is unquestionably an entertaining take on modern love, it feels more like the traditional movie romances that audiences gravitate to. With that in mind, I prefer Materialists to Past Lives. That’s not the last controversial take you’ll hear in this piece.

That said, the movie is not entirely successful. But what it does well, I liked. Song’s script is commendable if a little too monologue-heavy at times, and Chris Evans has returned to form after a dismal post-Avengers streak. He best succeeds as an actor when he’s in the extremes — ultra noble or ultra sleezy — or when he’s a loveable loser. Song utilizes Evans’s skills there to craft a character impossible not to root for.

The same, sadly, cannot be said for the other two performers. Pedro Pascal, a perfectly fine actor, gets much less to do in the film than I expected. And Dakota Johnson? Well, the less said, the better. To be brief, Johnson doesn’t have the skills as an actor to anchor a movie like this. We’re supposed to be following her journey. But how can we root for her if it's impossible to empathize with her? Johnson’s cold, detached style of acting does her no favors here.

And now, by process of elimination, you can probably assume where Life of Chuck lands: with a thud. A clanking thud. Don’t think I’m telling the truth? Well, folks will remember that I walked out of Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis last fall. I thought about doing so again more than once here. In fact, at one point, I was so bored with the tension-less, aimless, story-less series of moving images that I went to use the restroom just to do anything else. After the movie, my friend and beloved Cinemantics writer Graham commented, “If you just left and texted me when you got home, I wouldn’t have blamed you.”

Based on a Stephen King short story of the same name, Life of Chuck is utterly lifeless. It is visually flat. At best, it has the visual language of a bad hour of Netflix television. It is emotionally vacant. Writer-director Mike Flanagan recently said in an interview that he didn’t want to lean too heavily into one emotion or feeling because “that’s life.” Well, that may be life, but that’s not a movie.

It is also poorly acted. Karen Gillan and Mark Hamill especially gave two bad performances for different reasons. Gillan, who I like as an actor, is as flat as cardboard and colorful as a newly painted white fence. Hamill, on the other hand, hams it up with a bizarre hairpiece, an even more bizarre delivery style, and an accent that is best described as Foghorn Leghorn by way of Brooklyn. That’s not to mention a near constant narration by *checks notes* Nick Offerman who does not shut the fuck up. Seriously. In the movie’s quietest moments, where the emotion is all there and you just want to be with them in the silence, fucking Ron Swanson starts talking and I feel like I’m in a Parks and Rec episode.

The great sadness of this movie is that there are glimmers of a good movie — nay, a great, euphoric movie — in here, but not enough to recommend this to even my worst enemy. It’s ironic. For a movie that’s supposed to be life-affirming, it makes you wish it were all over.