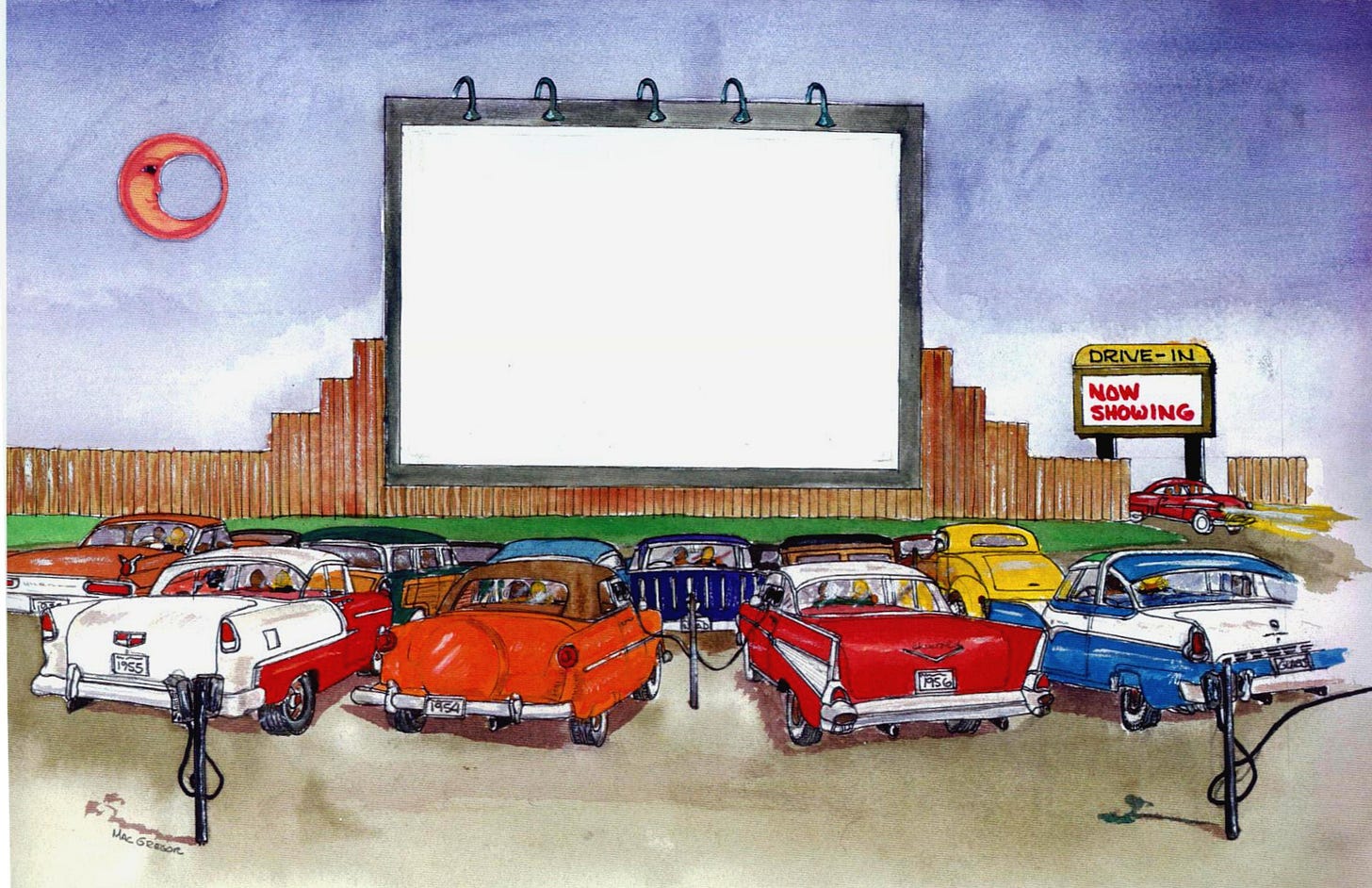

From time to time, Cinemantic’s four main contributors — Tyler MacQueen, Graham Piro, Caleb Boyer, and Daniel Mitchell — will jump on a call to chat about anything and everything movies. This month, we settle on what our dream drive-in double features would be.

TYLER: What makes an ideal drive-in double feature? Well, a few criteria spring to mind: They have to be (relatively) well-known pictures and they have to have some thematic thread that connects the two. But the movies also can't be too similar, or else the audience will get bored.

So, my double feature would be Jaws (1973, Spielberg) and Nope (2022, Peele).

Both are about the danger of spectacle told by two masters of genre and tension; one looks to the depths of the ocean and the other to the vastness of the night sky. One explores race and legacy in Hollywood, while the other is the template that all creature-based thrillers are copied.

Peele has even admitted that Nope is his attempt at a Spielbergian picture, even staging his finale at the Jupiter's Claim amusement park as a tribute to the blood-curdling finale of the first Summer Blockbuster.

Now, it's true that Jaws is much more straightforward and thrill-a-minute than the more contemplative and slow Nope, which makes it a natural contender to be the second half of the double feature. After all, it's better to go out with a bang. However, you can only appreciate Peele's sincere admiration for the Bard of the Sky if you watch his work, consider it, and then turn to Peele's response. It makes you appreciate both what has been made and what came before.

Plus, they're just really damn good summer movies.

CALEB: Since comparing Stagecoach and Mad Max: Fury Road a few months ago, the idea of companion films has intrigued me. My drive-in double feature is less dream and more nightmare: The Exorcist (1973, Friedkin), and The Autopsy of Jane Doe (2016, Øvredal).

In each film, the characters encounter supernatural evil, and their responses are similar yet different. When put together as a program, the tension between faith and science is more apparent. Seeking natural causes as an explanation for supernatural phenomena leads to bewilderment and deadly consequences.

In the Exorcist, doctors cannot explain the disturbing changes that young Regan (Linda Blair) experiences due to demonic possession. Similarly, a coroner (Brian Cox) and his son in training (Emile Hirsch) become increasingly confused as they conduct the autopsy of a ‘Jane Doe’ murder victim.

These men of science torture the material world with their scalpels and needles to uncover the secrets it reveals. When their findings lead to irrational explanations, unsatisfying answers follow.

Unable to supply rational theories and remedies, the doctors in the Exorcist refer Regan to a psychiatrist to avoid admitting defeat. They conclude her problem is of the mind, not the body.

In the Autopsy of Jane Doe, the coroner and his son do not have that luxury. The body is all they have to investigate, the material that remains after some essential part of us departs. The coroner’s pride refuses to give up despite setbacks at every incision, and he rejects multiple opportunities to leave his bafflement behind and go home with his son.

Knowledge is not always a good, especially when faith and sacrifice are ultimately the only efficacious weapons against supernatural evils.

Only the sacrifice of a father can stave off the demonic forces that torment them in both films. Together they show that self-sacrifice works, but it comes at a cost. In the closing scene of the Autopsy of Jane Doe, we hear a preacher proclaim, “the word of God is powerful,” over the static of a car radio. The station suddenly changes to a choir of children singing, “Open Up Your Heart (And Let The Sunshine In).”

It is very unsettling. It is also sobering because the characters in each film discover these things to be true, only too late.

GRAHAM: I recently sang the praises of Longlegs, one of the best horror movies I’ve seen in recent years. Longlegs wears its influences on its sleeve. The structure of the film, FBI agents pursuing a mysterious killer who conducts a series of seemingly unexplainable murders and leaves behind notes written in cypher, channels David Fincher’s Se7en and Zodiac. The FBI agent dynamic also feels drawn from The X-Files.

But the film Longlegs reminded me most of is more recent: David Prior’s 2020 The Empty Man, a now-cult movie that was buried on video on demand during the pandemic after a rocky production.

I didn’t see The Empty Man in theaters. Unfortunately, not a lot of people did. But it has gained a second life because of its surreal atmosphere, sense of cosmic dread, and Lovecraftian nihilism.

Longlegs and The Empty Man open on a prologue whose significance to the story isn’t unveiled until significantly later in the film. Longlegs’s opening jolts from quiet dread to shock abruptly. The Empty Man, on the other hand, spins out a 25-minute story involving four friends on a backpacking trip that slowly builds its tension to a brutal conclusion. But both prologues effectively set the tone for the rest of their stories, with Longlegs introducing its uncannily human villain and The Empty Man establishing the mystery surrounding the film’s antagonistic entity. And both pay off later in their stories, drawing together the events of the whole film.

Both films consistently place their protagonist in isolation, positioning them as overmatched against an unknowably larger supernatural force, giving both films a sense of mystery and dread as the viewer slowly understands that what the characters are witnessing isn’t quite explicable. And both films conclude with twists that reveal that the players closest to our protagonists are not what they seem.

What makes the two films an effective double feature is their suggestion that evil, otherworldly forces exist and are perpetually searching for vulnerable vessels (or tulpas) for entries into our world by targeting, or manipulating, human weakness. In Longlegs, the dolls; in The Empty Man, the titular Empty Man. They both get at an underlying sense that weakness may not just be negative in its own sake, but may actually be an opportunity for evil.

A double feature of Longlegs and The Empty Man wouldn’t leave anyone in a good mood when they leave. But they are two of the best horror films in recent years and suggest that horror is at its best when it’s unflinchingly dealing with the reality of evil in our world.

DANIEL: The hardest part of narrowing down a double feature is deciding on the genre. Blockbuster, comedy, action, superhero, thriller. Say it like Alex Trebek: “Genre”.

For two movies in one evening, both films should be around the 2-hour mark. That rules out most superhero and blockbuster movies, though an obvious choice for a drive-in experience. Sorry Top Gun: Maverick & Die Hard, you just missed the cut.

I have paired two of my favorite thrillers for the perfect drive-in double feature: Rear Window and Get Out. These films, from visionary filmmakers Alfred Hitchcock and Jordan Peele, delve into voyeurism, paranoia, and social commentary, offering plenty to chew on long after the credits roll.

In Rear Window, Hitchcock masterfully crafts a tale of suspense centered on Jeff (Jimmy Stewart), a photographer stuck in his apartment after an injury. With little else to do, Jeff begins watching his neighbors through his telephoto lens, turning casual curiosity into a dangerous obsession. As he peers deeper into their lives, Jeff becomes convinced that one of his neighbors has murdered his wife.

Despite the doubts of his girlfriend (Grace Kelly) and his nurse, Stella (Thelma Ritter), Jeff cannot let go of the suspicion. The tension in the film builds beautifully as his voyeuristic tendencies lead him further into a web of intrigue, culminating in a gripping climax. Rear Window is celebrated not only for its suspense but also for its innovative single-set design and its thought-provoking exploration of the ethics of watching others.

Get Out takes a different but equally unsettling approach. Directed by Jordan Peele, this horror film tackles racism with a sharp, satirical edge – and won the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay. What a great movie year 2017 was!!

In Get Out, Chris (Daniel Kaluuya), is a Black man visiting his white girlfriend’s family for the weekend. What starts as an awkward, uncomfortable visit quickly spirals into a nightmare as Chris uncovers the Armitage family’s horrifying secret: they have been abducting Black people and using their bodies as vessels for the consciousness of wealthy, older white individuals. Get Out boldly confronts systemic racism and the veneer of liberal tolerance, using paranoia to heighten the horror and deliver a scathing critique of racial exploitation.

With each viewing of Rear Window and Get Out, I focus on different characters or scenes – the hallmark of a classic film! While Rear Window is more of a mystery/thriller, following it with the horror/thriller Get Out feels the right call to ratchet up the evening. Both films, though distinct in style and era, use the themes of voyeurism and paranoia to craft unforgettable stories, making them an ideal pairing for a thought-provoking night at the drive-in. Not only would they be tremendous to watch at a drive-in, but these are movies that will endure the test of time.

Sit back, relax, and see you at the movies.