Breaking Down Requiem for a Dream's Incredible Split Screen Effect

Anyone divided against themselves cannot stand.

The split screen is as old as cinema. It is a combination of two or more shots presented simultaneously, whether visible or invisible to the audience. There are a wide variety of uses for the split screen.

Like convincing five year old me that Lindsey Lohan shared the silver screen with her actual, identical twin in the 90s remake of The Parent Trap.

Besides duping small children into believing falsehoods for many years of their lives, the split screen can be used to achieve certain visual effects, create complex shots, present multiple perspectives at once and numerous other creative applications.

StudioBinder has an excellent breakdown of the technique, and even mentions the particular use I wish to explore, namely the split screens featured in Requiem for a Dream.

"Requiem for a Dream" is a novel by Hubert Selby Jr., adapted to film by Darren Aronofsky.

The story follows four individuals whose lives are consumed by their addictions, illustrating how the characters' hopes and dreams become nightmarish realities as they spiral further into their dependencies.

It is a film I will never forget and never watch again. Its message is powerful and disturbing.

We all are susceptible to addiction and its consequences because it comes in many forms that often play into our hopes and dreams.

Whether it is obviously dangerous like drugs or seemingly innocuous like television, addictions, both big and small, can corrupt the good we seek in our dreams and find in our realities.

Aronofsky’s camera work and editing is unlike any other film I have ever seen. Much could be said about the various techniques used to enhance the storytelling and the relationship between characters, but his unique use of the split screen stood out to me.

Within the first few minutes of the film, a visible split screen appears between Harry Goldfab and his mother, Sara. It is jarring and takes you out of the film, but I suspect it is intentional.

Harry and Sara argue through a closed door, which functions as the split in the screen, creating the two different perspectives we as the audience simultaneously witness.

Sara locks herself in a closet away from Harry as he steals her television set. The TV is chained to the radiator because Harry has stolen and sold it numerous times to get money for drugs.

Harry yells at his mother for hiding and chaining up the TV because it makes him feel guilty for his actions.

The split screen allows us to view Harry’s and Sara’s reactions at the same time, but it is also a literal divide that represents the fractured nature of their relationship.

The next use of the split screen is the famous shot that StudioBinder mentions in their video overview of the technique.

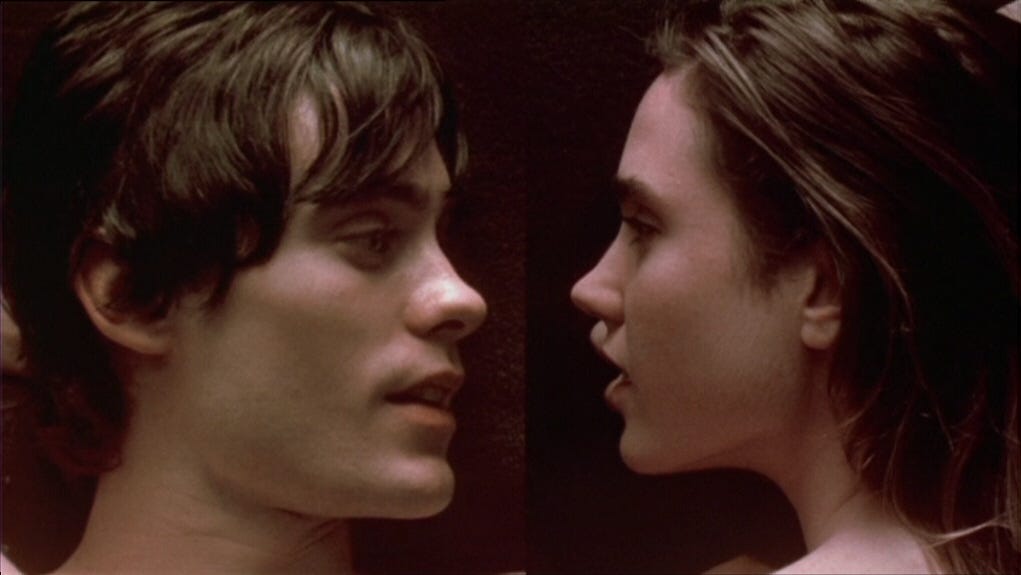

Harry Goldfab and his girlfriend, Marion, share an intimate face-to-face conversation as they lie next to each other in bed.

At first, the scene appears to be staged as a single shot since Harry and Marion are mere inches away from each other. As Harry and Marion reach out to caress each other, the dissonance of the shot becomes apparent.

The appearance and disappearance of disembodied hands at the center of the shot reveals a split screen.

Harry and Marion are shot individually and stitched together despite being close enough to warrant a single shot of them.

Like the split screen that reveals the division between Harry and his mother, another literal divide foreshadows the growing distance in Harry’s and Marion’s relationship over the course of the film.

Harry and Marion express their love for each other, and they dream about opening a store in the city together.

Their love is genuine, and their hopes are pure. All they need is some money and a bit of luck to turn their dream into a reality.

Their shared drug addiction, however, stands between them.

In their greatest moment of intimacy, the split screen reveals that Harry and Marion are as close as can be yet so far away from each other at the same time.

The distance between Harry and Marion grows literally and figuratively as their addiction corrupts their love, hopes and dreams.

The state of their relationship follows the timeline of the film, beginning in the bright, lively summer and ending in the bleak, dead winter.

In another famous shot, Harry and Marion are high and stare at the ceiling as they lie facing away from each other, surrounded by photographs they saved as inspiration for their store.

The potential reality of their dreams are all around them, but they cannot see them or each other.

As their money and drug supply begin to dwindle, withdrawal and desperation set in.

Harry suggests that Marion proposition her lascivious shrink in exchange for money because it is their “last chance to get back on track.”

Seeing no other way to escape their hopeless situation, she reluctantly agrees. Marion succeeds, but she is angry, ashamed and disgusted.

When Marion returns to her apartment, she sits on the other side of the couch opposite Harry. They sit in silence, unable to look at each other.

Their addiction and the terrible, debasing sacrifices it demands creates a rift between them, which grows as their supply of drugs inevitably runs out again.

Despite the money Marion acquired, there are no drugs for them to buy on the streets.

Blaming the world and each other, Harry and Marion fight over their bleak situation.

Yelling and screaming, Harry searches for something to write on.

He grabs a picture of him and Marion in front of the store they dreamed of owning.

On the back, he writes down the number of a drug dealer only interested in selling his product in exchange for sexual favors.

He hands Marion the photo and storms out of the apartment. It is the last time they ever see each other.

Harry goes on a roadtrip to Florida in an attempt to score drugs while Marion goes through withdrawal in her apartment alone.

As time passes and the symptoms of her withdrawal grow worse, she stares at the photo of her and Harry in front of the store.

She flips it over and looks at the drug dealer’s number.

Their picture and the phone number on the back of it symbolize how close our dreams and nightmares are to each other.

A single choice, big or small, can be all it takes to change life for better or worse.

The characters of Requiem for a Dream show how addiction destroys human freedom.

Any all consuming dependency corrupts the will to choose what is good.

Eventually, the only thing left to do is what you do not want to do. You come to love what you hate, regardless of the consequences.

You are split, divided against yourself, as illustrated by the fractured screens in Aronofsky’s film.

Great piece, man! Thanks for writing this.